The female reproductive system: Diagram, function, location & anatomy

Follows NC° Editorial Policy

At Natural Cycles, our mission is to empower you with the knowledge you need to take charge of your health. At Cycle Matters, we create fact-checked, expert-written content that tackles these topics in a compassionate and accessible way. Read more...

Key takeaways:

- The vulva and vagina are often used interchangeably, but are in fact different parts of the female anatomy

- There is a lot of variation in vulval anatomy — each vulva is unique to the individual

- Throughout our different phases of life, hormones can impact the structure of the female reproductive anatomy

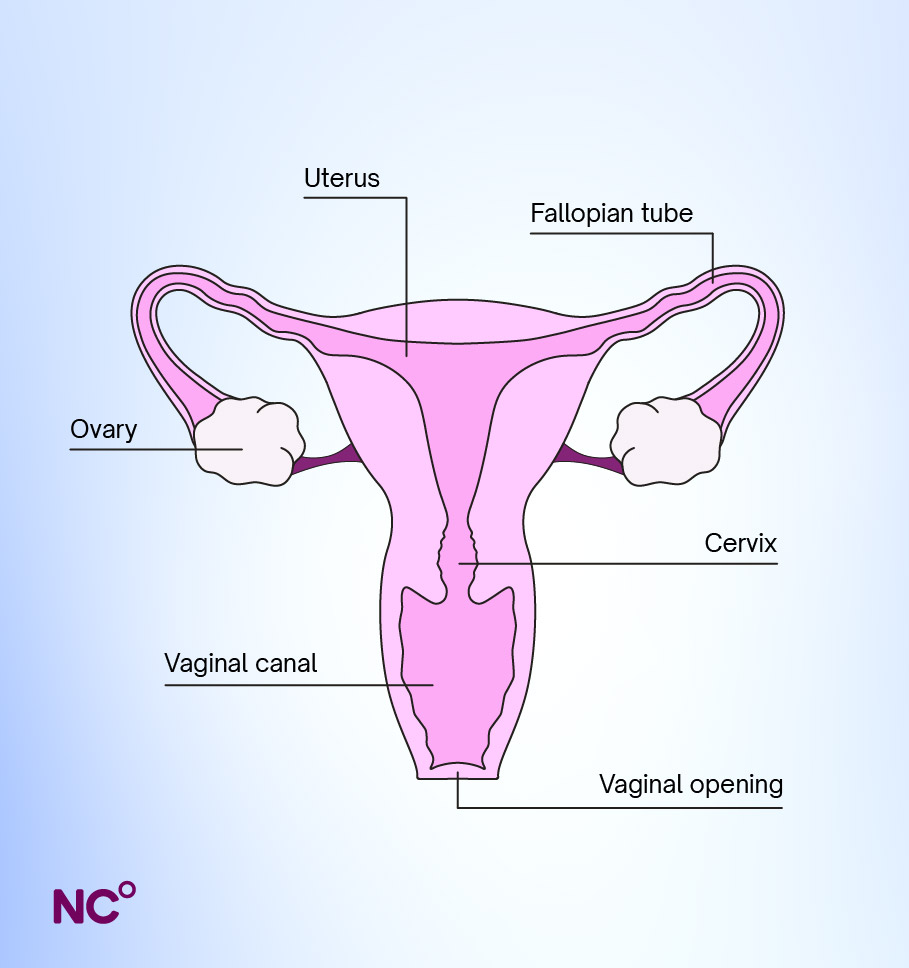

The female reproductive system is made up of both internal and external anatomy. These crucial parts play a role in menstruation, reproduction, sex, and pleasure. Below, we’ll delve into both the internal and external anatomy to help you understand their unique structure and function. If you’ve ever wondered what the difference between the vulva and the vagina is, or where exactly your fallopian tubes are located, you’ve come to the right place!

Female Reproductive Anatomy

There’s a whole lot going on out of sight when it comes to our reproductive anatomy. Let’s start by taking a look at the internal parts.

The internal parts explained

Vagina: The vagina is a small canal that connects the vulva to the more internal reproductive anatomy, like the cervix and uterus. The vaginal wall is made of three layers, which ensure strength and a certain amount of stretch to accommodate sex and childbirth, as well as different glands that contribute to sexual arousal [1].

Cervix: The cervix is a bit of fibromuscular tissue that looks like a ring with a hole in the middle, which connects the uterus and the vaginal canal [2]. Menstrual blood will flow from the uterus to the vaginal opening through the cervix, and during reproduction, the cervix allows sperm to enter the uterus and fertilise an egg. Throughout the menstrual cycle, the position of the cervix changes, and during childbirth, the cervix expands and ‘dilates’.

Uterus: The uterus is a muscular organ that is about the size of your fist. It is lined by the endometrium, a tissue that responds to hormones each month throughout the menstrual cycle. It’s the endometrium that sheds when you get your period, or in the event of pregnancy, this tissue helps support implantation. The uterus changes throughout your reproductive life, from puberty, pregnancy, perimenopause, and after menopause due to hormonal changes [3].

Fallopian tubes and fimbriae: Most of us have two fallopian tubes. These tube-like structures act as a vessel that carries eggs from the ovaries to the uterus. Contrary to what historic diagrams of the female reproductive tract have shown, the fallopian tubes are not attached to the ovaries, rather contain finger-like structures called the fimbriae that collect and direct the egg into the fallopian tubes, to eventually arrive at the uterus [4].

Ovaries: The ovaries serve many purposes in the female reproductive system and menstrual cycle. They produce hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone, which contribute to menstruation, pregnancy, and the menopause. They also store and release your eggs. During puberty, your ovaries will begin to release an egg each cycle and continue until menopause. It is possible that the ovaries release more than one egg at a time each month (known as hyperovulation), or that you experience anovulation, where you don’t ovulate at all during that cycle [4].

Hymen: The hymen is a thin piece of stretchy, perforated skin that typically surrounds the vaginal opening. It can naturally wear down over time, or more rarely, may tear down during vaginal penetration.

G spot: The G spot is an area inside the vagina that can feel pleasurable when stimulated. Though a highly talked-about structure when it comes to sexual pleasure, evidence to support the identification of a single zone is contradictory. Some say the zone doesn’t exist, whilst others have tried to pinpoint exactly where it may be [5]. Either way, there are many different positions you can try to stimulate the G-spot, for pleasurable sex.

The external parts

Now that we’ve covered the internal workings of the reproductive anatomy, let’s turn our attention to the bits you can see. To get better acquainted with your own anatomy, we suggest using a flashlight and a handheld mirror to get a closer look.

Vulva: The vulva is often incorrectly called the vagina, but in reality, they are different structures and have different functions. The vulva is the external part of your genitals, and includes the labia, clitoris, vaginal, and urethral openings [6]. Before diving into what these structures do, it's important to say that all vulvas will look different, and your vulva will be unique to you.

Labia minora & majora: The labia, otherwise known as the lips, are the skin folds around the vaginal opening. They offer a protective function, ensuring the labia majora are the outer folds, which feel fleshy and are often covered with pubic hair. On the other hand, the labia minora surround the vaginal opening [6]. For some, the labia minora will be hidden by the labia majora when standing, and for others, one or both may extend beyond the labia majora. In either case, these are completely normal —remember, every vulva is unique!

Clitoris: The clitoris is an important part of the female reproductive system, and unlike many other parts of the female reproductive system, it doesn’t play a direct role in reproduction. However, the clitoris is a key player when it comes to female pleasure, it contains over 8,000 nerve endings, and is the most erogenous (feel-good) part of the vulva [6].

Vaginal opening: The vaginal opening plays many roles. As part of the vulva, it has a protective function over the internal reproductive organs. The opening is where blood exists from each cycle during menstruation. When it comes to sex, the sensitive nerve tissue around the vaginal opening enhances pleasure during any kind of penetrative sex. Finally, if you have or plan to have children, it is the route through which the baby exits the body during childbirth.

Urethral opening: This is the opening through which urine leaves the body when you pee.

Bartholin’s Glands: Located near the vaginal opening, the bartholin’s gland releases fluids that lubricate the vagina when you’re turned on, or ‘wet’ [7].

Skene’s Glands: These can be found on both sides of the urethral opening. They produce a mucus-like fluid during sexual arousal and orgasm that helps to lubricate the vagina, and are further believed to lubricate the urethral opening to prevent urinary tract infections [6,8].

Mons pubis: The mons pubis, otherwise known as the pubic mound, is a bit of soft fatty tissue that covers the pubic bones, which is often covered in pubic hair. The mons pubis protects this area, and also contains glands which release pheromones, and play a role in sexual desire [6].

Anus: The anus is located below the vaginal opening, and is the opening at the end of the digestive tract where feces (poop) exits the body. The anus contains many sensitive nerve endings, and some people may also experience sexual pleasure from anal stimulation. Since the anus is not self-lubricating, if you do decide to try any type of anal sex, it’s important to remember that lube is your friend.

The hormones of the female reproductive system

We can’t talk about female reproductive anatomy without giving a nod to those all-important sex hormones. As mentioned above, the ovaries are responsible for producing the hormones estrogen and progesterone, but let’s look a little closer at how these function.

Estrogen plays many roles in the reproductive system, including involvement in the menstrual cycle and thickening the uterine lining during the follicular phase of the cycle, and supporting developments during puberty, such as breast development and pubic hair growth [9].

Progesterone plays a more dominant role in the second part of the menstrual cycle, the luteal phase. If after ovulation the egg is fertilized, the progesterone levels will remain high to help sustain the implanted embryo and support the early stages of pregnancy [10]. If the egg is not fertilized, the uterine lining sheds (you get your period), and progesterone levels decline.

Estrogen and progesterone production are stimulated by the release of other hormones from the brain, called luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). During the follicular phase, rising estrogen levels will trigger a surge in LH 1-2 days before ovulation, and cause the release of the egg from the ovary. FSH, on the other hand, causes the egg to mature prior to ovulation [11].

Get to know your body better with Natural Cycles

Thanks for reading — we hope you learned lots about the different parts of the female reproductive system and its anatomy! With knowledge comes power, and increasing awareness about female health is key to our mission here at Natural Cycles. Our FDA-cleared app can help you plan or prevent pregnancy and learn more about your body and pleasure along the way! Discover if Natural Cycles is right for you!

Did you enjoy reading this article?